Sandy's Written Creations

Writings by Sandra Harrison including poetry, essays, fiction, non-fiction; children's literatire.

White Plains Revitalization; Its Vanishing Past

In February 2019, one of White Plains’ older homes was demolished. Former Rocco Briante house was built around 1914. Rocco Briante was a builder of homes and other structures. House at 40 Chatterton Parkway had become a “zombie” property. Neglect obviously caused severe deterioration of not only the house but to the stone stairs that rose above the street.

The neighboring community of Battle Hill pressed for something to be done by White Plains (WP) and this was the result. The three-lot property was to be redeveloped into 6 apartments that the city approved some years ago (2017). The developer asked for an extension in March 2018 but due to money issues, the plan had never begun. Therefore, the building that was to be demolished became a problem as it was left to deteriorate. The property now seems to be up for sale. Without redevelopment, the grounds will continue to be an eyesore and danger to the community as has other areas around the City that have had demolished structures while the plans for redevelopment of the property seems to have been abandoned.

Former Rocco Briante House Demolished 2019

When a structure is created for a particular purpose, its design often reflects its purpose. But, over time a constructed building can lose its occupants and often a structure left empty is neglected. Without maintenance, repairs or updates a building will deteriorate. Older structures often become a burden to landlords not having the revenues to maintain them.

Owners might find that selling an underused, empty or older outdated structure the only way to recover their loses. The property might be sold to a developer with the intention of replacing it with something new or for them to renovate. Sometimes a repurpose of its future use is necessitated. A community’s zoning might dictate its replacement but a request for a zone change is usually made by Common Council since revitalization is needed for the City’s survival. But, often the character of a neighborhood is changed and urban blight creeps in.

White Plains (WP) is one of those cities that has undergone many changes during its long history from its beginnings in 1683. The railroad coming in 1844 from NYC had a huge impact on the small village of farms that reemerged to become the modern City that it is today. WP revitalized much of its Business District in the 1960’s & 1970’s by tearing down most of the area and rebuilding newer structures. As a result, many older structures were destroyed. Even today this process has continued and despite the formation of a Historic Preservation Committee in 2015 that identifies and gives landmark status to historic structures; many of our city’s older structures have been destroyed.

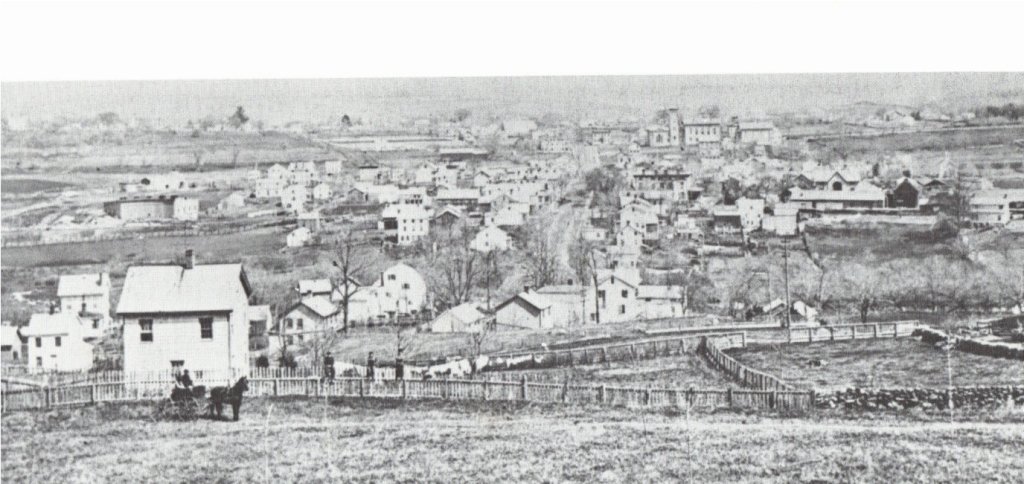

This picture from over a hundred years ago looks down from Battle Hill where the Down Town with Railroad Ave down the middle has today Main St up the middle. Chatterton House was in this picture and it is long gone. Picture is from the City Archives.

Gilbert Hatfield from John Rosch’s book from early 1900’s

One of the city’s oldest houses, the Gilbert Hatfield house at 636 on Hall Ave. was destroyed some years ago (around 2012) to be subdivided into two new structures. This house had predated the Battle of WP (circa 1770) and was used by Americans during battle. It was located on Hatfield Hill on what is today’s Hall Ave.

Gilbert Hatfield as it looked in 2012

The structure known as Soundview Manor that is on the National Registry of Historic places is in very bad condition. After B&B was closed the buyers of the house continued to ignore the structure that was damaged from leaking, and put in a plan with City to subdivided property and build new homes that included the demolishment of the older home. Historic Preservation Committee stopped the demolishment by giving the manor Landmark status. But with the continued deterioration, who knows the future of this former grand home. The new houses on the land that was once part of the Soundview Manor have been completed but the house is still under construction. Renovations are taking years.

Soundview Manor

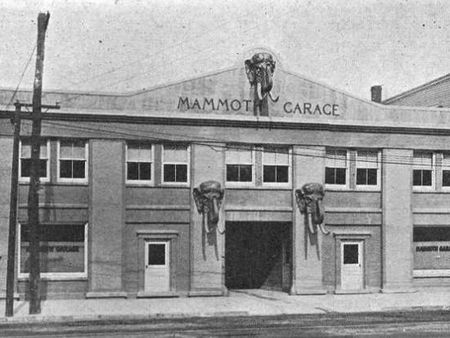

More recently, two buildings on Mamaroneck were leveled and one garage on Mitchell Place. The former Mammoth Garage was where the city’s first cars were made, and the building was over 100 years old. The building next to it that dated from 1928 was used by B Altman Department store when it opened in WP and years later by Alexander’s before it had its own home on South Broadway (repurposed for Westchester Pavilion and then razed around 2017 for new development that has stalled). The garage on Mitchell place also had a history of car making and racing. The Mitchell (now standing on the property that once was the Mammoth Garage and the building that was used by department stores) and was finally completed around 2022 (after years of construction that got stalled and restarted).

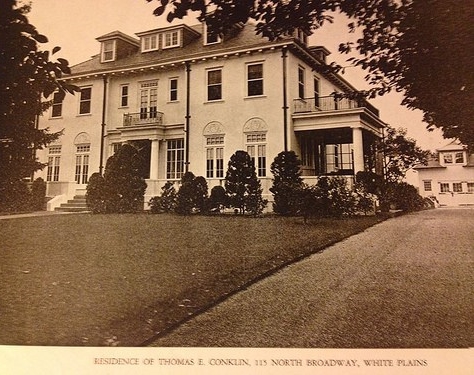

Twentieth Century House Thomas E. Conklin (dating from 1924) used by Elk Lodge at 115 N Broadway demolished for The Reed (2015, Vibe Living).

Another issue is long time businesses in WP leaving the City after decades. Before publishing my book, White Plains, New York: A City of Contrasts Georgeau Furs at 212 E Post had closed (2013) moving to NYC (in business for about 80 yrs). It is now a Barber Shop. When the White Plains Mall closed for redeveloped many of the former older businesses that moved to the building during urban renewal in Business District closed or moved to other places in WP or other places in Westchester. Hecht Hardware was the city’s oldest shop and it closed for good. Franklin Clocks moved to Elmsford and Chillemi Shoe Repair moved to Church St. Now the Galleria Mall has closed (1980- 2023) and is waiting for the plans for redevelopment by the owner. The parking garages are owned by the City of WP so they will be involved as well. Looks like the complex will be demolished and many in community are concerned about what will replace the mall that is basically in the middle of the Business District covering a large block of real estate.

Tighes Tavern on 174 Martine Ave closed its doors in Feb 2019 after being in business since 1935. It reopened as another restaurant.

Ridgeway Golf Club (1952) closed in 2011 (some sources say 2009) and sold its property to the French American School of NY (FASNY) (2010 or 2012). After a long process involving lawsuits, the school was given permission to open a middle and a secondary school in 2017 on some of the land and decided to sell the other areas but the plans for the school were abandoned. FASNY sold the entire property in 2021 that first started as Gedney Farm Golf Course in 1923 serving the Gedney Farm Hotel till in burned down in 1924. In 2022, new owners of former golf course have proposed putting in a new development of 98 single family homes (Farrell Estates). The former club house will be saved and used by the development. Plan calls for new streets as well. Many trees will be taken down. The homes will be selling at one million or more.

Now in danger of being leveled are most of the structures making up the former Good Counsel Complex at 52 N Broadway. Complex sold to a developer in 2015 with the closing of Good Counsel Academy and the elementary school moving on. Now, with Landmark status (2018) the plans have changed but not sure whether they have been approved.

New owner of YMCA on Mamaroneck Ave announced that they are planning to demolish building for a rebuild in 4/2019 but this did not happen till 2021.

YMCA Coming down Summer 2021

City’s website has an interactive section on projects proposed and approved by the Common Council. But has WP become addicted to new development sacrificing not only its history but causing more environmental issues? Most new developments approved and planned include luxury high-rise apartment buildings with or without retail space.

But the city is still oversaturated with office and retail space. There are many apartment units within buildings that are vacant. Some office buildings went through major renovations and the old AT& T Building is being repurposed into an apartment building. A new building was constructed in the large parking lot next to it.

There are signs all over the city advertising vacancies. City thinks that these projects will revitalize the business district and by bringing in more resident’s sales tax revenue will increase. But, for how long? Without a continual commitment to improve neighborhoods and the business district there will be a continual cycle of people, businesses and retail moving in and out of the city. Everything ages and the new once again becomes worn and run down. If the present owners can’t retain retailers now, how are they going to do this for a new development after a number of years when things get older?

The lack of convenient inexpensive parking, dirty unmaintained sidewalks and streets are just part of the problem. Construction often brings years of noise, pollution and congestion. Stalled projects create an eyesore in neighborhoods. City has started putting up signs outside parks or in green areas causing unnecessary blight and ugly clutter. Some neighborhoods outside of Business District feel like their areas are being neglected.

Recently, there has been movement on the part of the City to improve the business district but it is limited. The White Plains Public Library Plaza recently was renovated followed by a redo of the inside. The MTA has been working since 2018 on a 92 million renovation of the White Plains Train Station but was finally completed.

Luckily a number of businesses have chosen to renovate instead of asking for a rebuild. Some remodels include Gateway Building, Westchester One (westchesterine.com) and Target. The Westchester, The City Center and The White Plains Plaza (1 N Broadway; 445 Hamilton) have done renovations. The former American Cancer Society building at 2 Lyon Place was renovated (2018-19) after it was sold. But sidewalks and green spaces need attention as well. Crystal house seems to have done some major renovations of its outside where all the terraces are.

House in parking lot on E Post Rd came down.

There are a number of new buildings going up around the train station and plans to demolish and rebuild rentals on Water Street, Bank Street and N. Lexington where there was a parking lot. These projects are listed on the City of WP’s website under Proposals and Projects.

Even the Main Street Bridge over the Bronx River Parkway is going to be redone in 2023.

There is more information on WP Revitalization in other posts like Renovation the Westchester, and City Center Redo.

Book, White Plains, New York: A City of Contrasts

The book White Plains, New York: A City of Contrasts by Sandra Harrison was published in 2013. This website contains updated versions of the book broken into separate entries. In addition, other things about White Plains are included on the website but not in the book.

A full preview of the book can be found on Lulu.com the publisher of the printed and e-book formats of the book . One can purchase the book online through many book venders.

Copies of the book were donated to White Plains Public Library and some copies are available through the White Plains Public Library and the Westchester Library System. Copies were also donated to the White Plains Historic Society, Westchester Historical Society and the White Plains Public Schools.

Besides the website, a corresponding Facebook page with the same title as the book can be accessed for information about White Plains.

Reward Programs & Perks in White Plains

Offers by Government/Businesses/Restaurants are available in White Plains (WP):

Discounts:

- BID Discount Card: sign up online and use card at various places for discounts.

- Target (sign up required with use of their credit card, 5% off)

- Stop & Shop; Shoprite: Offer discounts/coupons with card that requires sign-up.

- City Center 15 Showcase: Offers discounts/ perks at certain times and/or for certain groups (see online: Bargain Tuesdays, Senior Wednesday, Popcorn Club & Mom’s Night Out)

- Verizon Discounts for certain government, corporate, educators and military personnel.

- Sprint discounts for military

Reward/Loyalty Programs:

- Iron Tomato offers a free sandwich or salad after 8 buys of either salad or sandwich. Card punched for each buy at cashier.

- Showcase Cinema: Sign up required but earn points for free movie; food.

- Fridays Restaurant (sign up online with app required)

- Nordstrom Reward Program: online sign up

- Bloomingdale’s Loyalty Program: Sign up at register or online.

- Barnes & Noble: Discounts for members at $25 a yr. Discounts for educators, military, corporate groups and gov employees also offered.

- Whole Foods-App online gives coupons/deals.

- City Center and The Westchester have websites/Facebook pages that offer events and deals.

- Container Store: POP! Reward program. No fee.

Parking/Rides:

- City Fresh Market: Free shuttle ride spending $100; free delivery of $40 orders

- Metro North Discount off peak hrs & for seniors/disabled.

- Bee Line Bus discounts for seniors/disabled with Metro cards.

- Discount $75 a yr permit for residents parking in certain garages (Lyon, Trans Center, Galleria lots, Library, Main St, Chester/Grove; Longview) M-F 8pm to midnight; Weekends 10am-midnight.

- Free parking during storms when announced (sign up for alerts online).

- Shoprite: free 1 hr parking

- Wholefoods: free 1 hr parking

- Westchester Road Runner: free 1 hr parking

- Zipcars: Shared cars that you drive from Hamilton/Main Garage as a member with sign up online at White Plains website under “Our Community.”

- Electric Vehicle Charging for a fee at garages: Lyon, Galleria, Hamilton/Main, Longview/Cromwell.

Free Services/Things:

- TILI (Take It-Leave It) Shed: Gedney Way Recycling Center April-Oct Wed (2-4:30); Sat (9-12), Free stuff.

- Museum Passes: White Plains Public Library (WPPL) requires sign up.

- Charging for Cell Phones: City Center, Galleria; WPPL.

- Free Wi-Fi at various stores, malls and WPPL requiring sign up.

- Books, DVD’s, CD’s, Classes & Heritage Searches at WPPL. Requires card. Some services are available online.

- Free firewood, mulch, compost at Gedney Way Recycling Center.

Free Newspapers:

- Online: Patch; Daily Voice

- Westchester Parent, Family

- White Plains Examiner

Information will be updated as things change or become known.

Notable Afro-Americans of White Plains

Copied here is information from handout given out at White Plains Local History Roundtable Feb 2018.

NAACP in area covers Greenburgh & White Plains (WP). Housing in WP was segregated and Battle Hill was part of Greenburgh till 1916 when WP annexed the area as a City.

Many Afro-Americans lived in the Business District till Urban Renewal (1960’s through 1970’s) that demolished much of Business District. Winbrook Public Housing Development (1949) remained. In the last decade, the redevelopment of Winbrook begun. Called now Brookfield, one new building The Prelude was completed but demolishment of the older buildings and construction of the second phase has yet to start. WP Housing Authority manages the development.

There are other affordable income buildings in the City (DeKalb, Lake and Ferris) but many blacks and black businesses were driven out during Urban Renewal. Some businesses went to WP Mall.

The use of Affordable housing is now the preferred word for housing for lower income residents. Newer buildings constructed in designated areas of the City are required to have affordable units. In the construction of City Center apartments, Trump Tower, The Lofts, and One City Place, and then the Ritz Carlton Residences by Cappelli Construction affordable housing was placed in a separate structure under the NY Sports Club called The Summit at the City Center.

The book On the Streets Where We Lived published in 2011 by Roots of White Plains, Ltd. (established 2007 at 23 Montgomery Ave in Elmsford) and Harold Esannason is available at the library. It is a pictorial study about the experiences of Blacks in WP from 1900 to 1960.

Rosa Kittrell

This a copy of the text from Ben Himmelfarb’s blog on Local History on Rosa Kittrell for which White Plains (WP) named one of its parks :

Local History: Rosa Kittrell

By Ben Himmelfarb

October 10 has been designated World Mental Health Day by the World Health Organization. In honor of it, here is a story about a White Plains resident whose activism on behalf of people with mental illness had a national impact.

Rosa Kittrell worked hard to redefine the way we view and treat the most vulnerable members of society. Through her tireless activism, personal struggles with mental illness, and belief in the power of education, Kittrell developed a motto: “Others, Lord, others.” Like so many black women in America, Kittrell was intersectional in her activism before anyone ever heard of that term. She recognized the ways sexism, racism, class oppression, and stigmatization of mental illness operated to prevent her from obtaining help and fulfilling her dreams. Although she was not subtle about her frustration with systemic oppression and the ignorance of individuals, she spent most of her time engaged in helping others and trying to expand the boundaries of people’s compassion.

Kittrell was born in Henderson, North Carolina to James Lee and Alice Mills Kittrell. Her father was in the agricultural products business. During high school, she started working at a local YWCA and that inaugurated her interest in service to women and children. Rosa pursued graduate level education, graduating from the Hampton Institute and the Bishop Tuttle School for Social Work. Once out of school, she worked at a community center in North Carolina. It was while she was recovering from a surgery in North Carolina that she “realized that something was wrong” with her mind. She wrote a heart-wrenching account of her mental illness in the December 1943 Club Dial, published by the Woman’s Club of White Plains (and available in the White Plains Collection!).

Kittrell’s journey began while she was recovering from a surgery in a hospital and felt “some inner force” pushing her away from the people around her. Anti-social, negative feelings were novel to her–she was, after all, a social worker who dedicated her life to helping other people. Laying trapped in hospital bed, she felt she had “a normal self and a new abnormal self.” Her disturbing condition was exacerbated by the way people suffering with mental illness were treated in the 1930s. Her surgeon came into her room and gave her “a strong scolding” about her behavior towards nurses and refusal to eat. “Not once did he ask me why I was acting the way I was,” Kittrell reported. Isolated from family and any professionals who knew how to help her, Kittrell felt strongly that she “was no longer of any use.”

Club Dial, December 1943

She was eventually sent home from the hospital, having completed a physical recovery from her surgery. She isolated herself at home, missed work, and started having bouts of vomiting. She returned to the hospital and was quickly dismissed because no physical ailment could be detected. Home again, she became suicidal and was re-admitted. She began having spells of violent behavior and was regularly sedated for six weeks. Of her first harrowing experiences as a psychiatric patient, she wrote, “I longed for someone to whom I could talk, but no one would talk to me… I felt alone in a world where there were many strange people.” It would be years before her feelings were validated and she was treated with respect for her well-being.

Trapped at home, unable to work, receiving comments from doctors to “snap into” normal life again, Kittrell left North Carolina and moved to White Plains. Even with her professional, educated background, Kittrell was only able to work as a domestic–a position held by many black women in Westchester at that time. In White Plains, she “continued the same hysterical hours, but kept them hidden.” She consulted a lawyer in an attempt to bring a suit against her former employers in North Carolina who shunned her after she began having psychiatric problems. Rather than pursuing the case, the lawyer suggested she see a Dr. Brennan at Grasslands Hospital. Kittrell was frustrated by the lawyer’s response, but did not realize that collaboration with Dr. Brennan would change her life (and the lives of many others) for the better.

A different psychiatrist at Grasslands (not Dr. Brennan), suggested Kittrell be committed. She resisted for fear of being “branded as crazy for always.” Her fear was understandable–last time she submitted herself to psychiatric care, she was tortured and fired from her job. After a few weeks, however, she relented and voluntarily committed herself. She was placed in a “pack” and subjected to four hours of continuous baths, an antiquated and ineffectual treatment. She was sedated and given the primitive and often unhelpful medications available at the time. Again, she was “baffled, frustrated” by a system that treated people with mental illness horribly and doubled the misery of African Americans already suffering under discrimination and oppression in society at large.

A ray of light for her was Clifford Beers’ seminal book A Mind That Found Itself, which told of his struggles earlier in the 20th century. Beers dedicated his life to bettering the fate of people with mental illness. Like Kittrell, Beers came to his advocacy work through personal experience, having spent time as a patient in facilities with abysmal conditions. He was the main force behind the mental hygiene movement that advocated for more humane treatment and thorough understanding of those with mental illness. Kittrell read A Mind That Found Itself and wrote to Beers for hope and direction, eventually meeting with him twice. Through a total of 21 admissions to different hospitals and Beers’ influence, Kittrell developed a critical consciousness about the mental health system and became determined take action.

Reporter Dispatch, January 22, 1965

She felt society “hadn’t learned to face mental illness, and this condition was doubly hard for a Negro.” Her diagnosis of society’s ills had three parts. First, the lie “that Negroes don’t go crazy” must be disproven. Second, people must fully “recognize the fact of mental illness” and accept responsibility for discovering solutions. Third, black Americans with mental illness were forced to “do battle in… an alien white world where no opportunity is given for members of his own to help him.” Kittrell’s community in North Carolina was unable to help her, and she fared no better in the supposedly less-segregated north. Her drive to provide better treatment for all people, but especially black Americans, with mental illness led her, finally, to Dr. Thomas P Brennan.

It took four years for Kittrell to approach Brennan as a collaborator in her activism. She “identified him with the white race,” but was eventually won over by “his real love of all races and a sincere desire to help the mentally ill.” Together, they set up the White Plains Mental Hygiene Group, which had specific goals. The group sought to create a psychiatric hospital for black Americans attached to a “Negro medical school” and to create trainings for the enlightenment of existing psychiatric professionals. Kittrell and Brennan’s campaign was extremely successful in creating a movement for change. Together, they sponsored and attended conferences in Alabama, North Carolina, Washington D.C., Oklahoma, Georgia, and West Virginia, leaving new, local mental hygiene groups in their wake. Like Johnny Appleseed but with a social conscience, Kittrell traveled to spread her progressive message that people should “look upon mental illness as they do upon physical illness,” presaging our contemporary understanding of mental illness.

In addition to putting her energy into national reform efforts, Kittrell dedicated the majority of her time in the late 1940s until her death in 1967 to social activism in White Plains. At a 1965 dinner to honor her work, international medical rights authority and Scarsdale resident Howard A. Rusk, Jr., said, “She was way ahead of her time in her foresight and knowledge of needs in the community.” Kittrell’s “war on poverty” started long before Lyndon Johnson declared the eradication of poverty a national priority.

Reporter Dispatch, January 24, 1967 (1 of 2)

In 1945, Kittrell established the Carver Community center to serve young people in downtown White Plains. In 1952, she founded the Kittrell Nursery School for the children of working mothers. Its original location, at 60 West Post Road, was a storefront space. After the Rochambeau School was closed when the Racial Balance Plan was enacted, Kittrell merged with the White Plains Child Day Care Center in the former elementary school. Because the school served families who could not afford to pay very much for child care, it struggled financially. As Kittrell’s obituary noted, her “impulsive, outgoing, total concern for the children in her care” was sometimes an impediment to garnering mainstream financial support for the school. Eventually, Kittrell was relieved of business responsibilities and able to “concentrate on the school’s program,” which included prayer, food, and socialization activities. Kittrell’s passionate activism “resulted in considerable trial and tribulation” in her life. Her sister, Flemmie Kittrell (Director of the Home Economics Division of Howard University), said, “One of the weaknesses of Rosa is that she is always looking around to see who in the community is poorer than she is, and trying to find out what she can do for them.”

Kittrell usually favored action over talk. She did, however, offer this when she was honored for her work by the community in 1965: “You have no idea how this makes me feel on the inside, but I give all the glory to God. Many hours we have prayed and said, ‘Lord, here is a parent who wants to do the right thing for the children but who just can’t today.’ Let us try awfully hard to be very real now, because we are working with human beings and we have to meet them on their level. But let us also cling close to God, for we have not experienced Him until we have done something for someone else.”

Reporter Dispatch, January 24, 1967 (2 of 2)

Her style of activism was defined eloquently by Prince P. Barker, a colleague in the mental hygiene movement from Tuskegee University. He described their reform efforts as the “correlated use of the social sciences as a tool for the promotion of the mental efficiency and healthful living on men and mankind.” Kittrell acknowledged that mental illness and poverty were not issues that could be improved through strictly technocratic solutions. For her, race, class, gender, faith, and the realities of everyday life all had a place in discussions of social problems. In living by her motto of “Others, Lord, others,” she acted with an authority born of experience.

October 10, 2017

Gaudier-Brzeska

Intriguing artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915) lived a short full life before dying on the battle field in Europe during World War I at 23.

French born sculptor had a platonic but personal relationship with Sophie Brzeska, a polish poet and writer. He adopted her surname.

The couple moved to London in 1910 till he enlisted in French Military where he died. Both suffered from mental illness.

Henri left a large body of work including drawings, paintings and sculptures. He was part of the Vorticism movement.

He and Sophie were the subject of movie ” Savage Messiah,” a play and non-fiction books.

Helpful Resources for White Plains Residents in Need

“Who ya gonna call?” What can a person do when they need help? There are a number of organizations and places that people can reach out to help. Listed here are those available to White Plains (WP) residents.

Information listed here does not guarantee you will get the help you expect or need. The list is incomplete and some listings might have changed. Many organizations have multiple purposes & services not all listed here.

Abbreviations used here: WP-White Plains, WPPL- White Plains Public Library, WPETC– White Plains Education Training Center.

Adults/Seniors:

- Aging in Place Home Repair Program through Westchester County Habitat for Humanity http://www.habitatnycwc.org/aging-in-place, AgingInPlace@habitatnycwc.org, 914-240-7003

- Senior Center WP: 65 Mitchell Pl, M-F 8:30am-4:30pm, (914) 422-1423, for classes, events; wellness support. Daily meals weekdays ($3 with reservations) (914) 422-1423, 11:30am-12, Transportation to Center ($1 with reservations each way with 9 am pickup, 1pm return to homes), Bus to International Farmers Market (Wed with 9am bus; back to Center at 10:30 with reservations), Bus to Supermarkets on Thurs (Stop & Shop or Shoprite) with early bus 9:15 & back to Center, Coupons to market for eligible recipients, Thrifty Boutique Shop (10am-2:30), Medicare Counseling (65 & above to eligible recipients).

- AARP Foundation: Tax prep (WPPL & WP Education Training Center)

- My Second Home Intergenerational Adult Day Program: Dementia care, (914) 422-8100, 106 N Broadway, fsw.org.

- WP Yellow Dot Program: Notification assist for seniors & others to contact named persons for medical emergency.

- Slater Center Drop-in Center: (M & Thurs 11am-2pm).

- Senior Benefits Info Center: httsp://www.westchesterlibraries.org, e-mail sbic@wismail.org, 914-231-3260, Medicare info.

- Westchester Jewish Community Center: 845 N Broadway, ( 914) 761- 0600, at info@wjcs.com. Mental health, trauma, disabilities, youth, home care and geriatric services.

- Administration on Aging: acl.gov. Promotes the well being of older individuals by providing services & programs that helps them live independently in their homes & communities.

- Eldercare Locator: (800) 677-1116 M-F 9am-8pm, eldercarelocator@n4a.org., eldercare.gov. National free service to help older persons live independently & support caregivers. Resource info.

- Dorot Westchester: Alleviates social isolation & provides concrete services for older adults, aging services, volunteerism inter-generational connections. dorotusa.org/site/PageServer?pagename=westchester_D#.Wd57IEBLXeQ

(914) 573-8906, 171 West 85th Street New York, NY. - US Social Security Administration Office, 97 Knollwood Rd: http://www.cityofwhiteplains.com/914 422-1411

- Westchester County has automated weekly updates sent to those interested in various areas by e-mail concerning programs/events/services. To sign up for senior info go to https://seniorcitizens.westchestergov.com/news-and-events/aging-network-news-sign-up. For other areas see the county website and signup for each area of interest www.westchestergov.com.

- RideConnect, volunteer driver/referral program serving adults age 60+. Volunteering is flexible & every single ride is appreciated, 914 242-7433, www.rideconnectwestchester.com

- CarePrep Westchester: Program to Help People Prepare for the Journey Ahead…Caregiving. Mission of CarePrep-Westchester is to educate future and current caregivers about the myriad aspects of caregiving by offering the resources they need to prepare or continue to provide the best care possible for their loved ones and for themselves. To learn more, click here. CarePrep Westchester website offers free Webinars on Demand. To access, click here.

- Carfit. Helps older drivers find a car for good fit and how to help adjust car for changes as people age. car-fit.org.

- WESTCOP Benefit Enrollment Center helps seniors identify and apply for various benefits 914-592-5600.

- Westchester County Department of Senior Programs and Services (DSPS), Court hearings, building department enforcement and other critical housing issues contact Ronnie Cox at 914-813-6444 or email at rqcb@westchestergov.com.

- NY Connects at DSPS to identify financial benefits, services; resources: 914-813-6300.

Adult Clothing:

- Coachman Family Center: 123 E Post Rd, (914) 949-1000.

- The Career Closet (WPETC) providing clothing for interview & employment..

- Hebrew Institute of White Plains Back Door Thrift Shop, 20 Greenridge Ave, (914) 358-5575, hiwp.org/resources/thrift-shop/ Inexpensive used clothing, jewelry & other items. Hrs: Tues, Wed &Thurs (10am-2pm).

Caregivers Help:

- Livable Communities Caregiver Coaching + (L3C): Provides training for volunteers of family caregivers for seniors; disabled. One-on-one support coaches enable caregivers to make more informed decisions to meet challenges/responsibilities. For a Livable Community Caregiver Coach, contact Colette Phipps (914) 813-6441; cap2@westchestergov.com

- Care Connections Program, 914-366-1199, caregiver@northwell.edu

Children’s Clothing (0-18):

- Jewish League of Central Westchester (JLCW) Teen Boutique: April 21, 2018 at Westchester County Center (items for 13-19yr olds) (914) 723-6120, https://www.jlcentralwestchester.org, or e-mail at jlcw@verizon.net.

- Sharing Shelf of Family Services of Westchester: 7-11 S Broadway, (914)-948-8004.

- Back to School Programs: Kid’s Kloset through Westchester Jewish Community Center (JCC), 845 N Broadway, wjcs.com/kids-kloset, (914)-761-0600

Children Programs (0-18):

- Youth Bureau Programs (please check for updates and services still being given: 11 Amherst, (914)- 422-1378, whiteplainsyouthbureau.org, Special Events; trips, camps, health, jobs; mentors, Camp Central for Spring/Winter (at Church St School with fees), Middle School Stem Camp at Church St, Bits N’ Pieces (Church St School), Summer Enrichment program (fees with scholarship offered), Health & Wellness Summer Fitness Boot Camp (free YB), After School Connection at various schools & Slater Center, Youth Employment & Volunteer Opportunities; Enrichment & Personal Growth Activities, Teen Lounges at Battle Hill and Eastview for after school; weekends, Youth Leadership and Court. Teen Lounges at Battle Hill & Eastview for after school; weekends, Youth Leadership and Court programs.

- SAT & College Preparation (for 11-12 grades), letsgetready.org (fees charged)

- WPPL The Edge: at edge.whiteplainslibrary.org, (914) 422-1481, Steam, Coding Camps & Summer Reading Game

- The American Camp Association Camp Scholarships: acacamps.org, they offer a dependent care flexible spending account.

- Child & Dependent Care Tax Credit: Tax credit up to $3000 per child but called at $6000.

- Born Learning: free activities & games to prepare for school.

- Trove at WPPL: trove.whiteplainslibrary.org & The Edge (teens)

- WP Parks & Recreation Dept. Playing fields, playgrounds & pools (914-422-1339).

- Passage to Excellence After School Program: 1 Fisher Ct, for Winbrook; Brookside resident children.

- Delany Center for Educational Enrichment at Pace University: Programs for children after school, Sat and summers (fees charged). 78 North Broadway, (914) 422-4135, thedelanycenter.com; facebook.com/thedelanycenter, e-mail: mdelany@pace.edu, the delanycenter.whiteplains@gmail.com.

- Head Start Family Services of Westchester: 1 Summit Ave, fsw.org/our-programs/early-childhood/head-startearly-head-start.

Children in Crisis:

- National Runaway Safeline: (733) 880-9860, (800) 786-2929 (24/7), 1800runaway.org. Federally designated national communication system for runaway and homeless youth.

Cultural Groups:

- Haitian Resource Center: Slater Center, 2 Fisher Ct, (914)-648-6311. Tues-Thurs 11am-2pm.

- Centro Hispano: 346 S Lexington Ave, (914) 289-0500, elcentrohispano.org.

- White Plains & Greenburgh NAACP: Website wpgbnaacporg.wordpress.com, e-mail whiteplainsgbnaacp@gmail.com, (914) 682-5998.

- The Loft: 252 Bryant Ave, http://www.loftgaycenter.org., (914) 948-1932.

- Westchester Hispanic Coalition: 46 Walker Ave, (914) 948-8466.

- Urban League-Westchester County: Helps African Americans achieve economic self reliance, parity power & civil rights, 61 Mitchell Pl, (914) 428-6300 http://nul.iamempowered.com/affiliate/urban-league-westchester-county-inc.

Diapers:

- Junior League of Westchester (JLCW): Diaper Bank, jlcwduaperbank@gmail.com, (914) 723-6442

Disabilities:

- Andrus Home: 19 Greenridge Ave, (914) 949-7680, andruscc.org/

- Arc of Westchester: arcwestchester.org, 265 Saw Mill Rd (9A)

- Blythedale’s Children’s Hospital:

- Westchester Independent Living Center: wilc.gov, (914)-682-3926, (914)-259-8036 (VP/TTY),

- Hawthorne, NY 10532, (914) 949-9300 or (914) 428-8330.

- Children’s Rehabilitation Center: 317 North Ave, (914) 597-4000 Physical, occupational, and speech and language therapy.

- IDEA: Ages 0-21: sites.ed.gov/idea

- Social Security: SSI and SSD: ssa.gov/benefits/disability/

- Medicaid through Westchester County: 85 Court St, (914)-995-3333 (M-F 8:30-5)

- Rapid Recovery Program: Registry for vulnerable children (i.e. autistic) or adults (dementia) providing information for emergency response. (914) 422 8514, wppublicsafety.com.

- Westchester Jewish Community Center: Mental health, trauma, disabilities, youth, home care and geriatric services, 845 N Broadway, 914-761-0600, wjcs.com.

- Office of Disability Employment Police: (202) 693-7880, (866) 633-7365, TTY (877) 889-5627, dol.gov/odep. Ensuring people with disabilities are integrated in the workforce.

- Veteran’s Employment and Training Service, (866) 487-2365 TTY (877) 889-5627 Provides resources to prepare and assist veterans to obtain meaningful careers and maximize their employment opportunities, dol.gov/vets; veterans.gov.

- Abbott House: Helps children and families in need and people with developmental disabilities, 100 N Broadway, Irvington, (914) 319-1609, abbotthouse.net/.

- Westchester County Office for People with Disabilities @https://disabled.westchestergov.com/

- Westchester Disabled on the Move, 984 North Broadway, Suite L01, Yonkers, NY, 10701, 914-968-4717, http://www.wdom.org Provide advocates for consumers and work to ensure that public/private programs/services are available to Disabled to encourage independent community living. Help with obtaining/maintaining benefits for Social Security Disability, Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid, Medicare, Personal Assistance; other forms of public assistance. Help assist those returning to work with Social Security Work Incentives

- Westchester Lighthouse: 170 Hamilton Ave, Martin Yablonski, myablonski@lighthouse.org Website: http://www.lighthouse.org. Helps people of all ages who are at risk for, or who are experiencing vision loss. Through services, education, research and advocacy, the Lighthouse helps people with low vision and blindness live safe, independent and productive lives.

Education:

- Learning English at White Plains Public Library (WPPL)

- Learning to Use Computers Senior Center/WPPL

- Ruth Taylor Scholarships: Assistance to becoming Social Worker

- White Plains Education Center (WPETC): 303 Quarropas St (M&F 9am-5pm, Tues-Thurs 9am-8pm), 914-422-8200, website: whiteplainsny.gov/index.aspx?nid=636, e-mail: wpetc@whiteplainsny.gov.

- Southern Westchester BOCES Adult Education: adulted.swboces.org, Center for Adult & Community Services, 450 Mamaroneck Avenue, 2nd Floor Harrison, NY 10528, (914)-592-0849. Programs are available at different locations including Rochambeau Alternative HS, 228 Fisher Ave. (M&W 6-9PM), and El Centro Hispano 346 S Lexington Ave.

Energy:

- Building Dept. of WP: Heat & Water Concerns:(914) 422-2269 (normal business hrs; Police (914) 422-6111 (weekends, nights and holidays)

- Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) Utility and home heating assistance through county social services 914-995-3333.

- New York State Energy Efficiency Programs, Emergency Home Repair Program for the Elderly (RESTORE), Healthy Homes (New York State Department of Health), New York City Better Business Bureau, Upstate New York Better Business Bureau; Weatherization assistance providers.

Emergency Housing:

- Grace Church Community Center: Samaritan House Homeless Shelter for Women, 33 Church St, (914) 948-3075 (Drop In Center).

- Open Arms Homeless Shelter for Men and Drop In Center on 86 E Post Rd, (914) 948-5044.

- Westchester County Emergency services for Adults and Families: Office of Temporary Housing Assistance, 85 Court St, M-F 8:30-5.

Warming/ Drop In Centers: (914) 995-2099 on weekends & after hrs. Coachman Family Center: homeless shelter for families mostly: westhab.org, (914) 946-3371. - Lifting Up Westchester: 35 Orchard Ave, 914-949-3098, liftingupwestchester.org. (Homeless services on streets).

- American Red Cross: Offers help during disasters, 914-946-6500, redcross.org/ns/apology/disaster_homepage.html

Families:

- Family Services of Westchester: Provides a variety of services for families, veterans, individuals and older adults for health, employment and everyday living needs, 1 Summit Ave., fsw.org/, (914) 948-8004.

Financial Advice/Aid:

- At work ask about pre-tax money programs to be used for child and adult care and/ or health care.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau: Federal agency to protect financial rights of consumers, assistance on credit, loans, banking, ID theft, credit repairs 855-411-2372; consumerfinance.gov.

- Credit Counseling: Claro limited legal services for credit defaults 877-574-8529 http://www.claronyc.org/claronyc/Westchester/westchester.html

- Financial Counseling Association of America helps, recreate; implement a credit repair plan 800-450-1794 https://fcaa.org.

- Office of Child Support Enforcement, Administration for Children and Families, (202) 401-9373, e-mail ocsehotline@acf.hhs.gov and acf.hhs.gov/program/CSS, assures financial and medical support to children by locating parents, establishing paternity; enforcing support obligations.

- National Foundation for Credit Counseling: Counselling for debt reduction, better management, improved credit standing 800-388-2227 or 855-939-0724, https://www,nfcc,org.

- Smart Seniors: NYS Attorney General’s Office alerts/publications to help to seniors on financial matters, scams.; fraud, ag.ny.gov/smartseniors.

- United Way’s Financial Ed Program: Workshops, online resources; coaching on personal finances. uwwp.org/fep.shtml.

- YWCA: 515 North St, (914) wcawhiteplains.com (914) 949-6227. Empowerment and Economic Advancement.

Food Pantry & Help:

- Feeding Westchester: feedingwestchester.org, (914) 923-1100: Senior Grocery Program, Kids Backpack Program, Mobile Pantry: (914)-923-1100, mobilepantry@feedingwestchester.org.

- Ecumenical Food Pantry: 2 Fisher Circle, (914)-563-2960, Fri 8-10am.

- First S.D.A. Church Food Pantry, 180 Juniper Hill Rd, (914)949-6816 (Sonya Ennis), e-mail-slennis240@gmail.com.

- French Speaking Baptist Church Food Pantry, 237 Ferris Ave, (914) 946-1117, Hrs.- 2nd Sat 12:30-2pm.

- Houses of Worship have pantries so check their websites.

- Kol Ami Pantry that serves members, guests. (914) 949-4717; info@NYKolAmi.org

- Kosher Food Pantries: https://www.metcouncil.org/kosher-food-network

- NY Benefits: mybenefits.ny.gov.

- Ridgeway Alliance Church Food Pantry: 465 Ridgeway Ave, 914-949-3714. Hrs are as needed.

- SNAP: Westchester Dept. of Social Services, 85 Court St, (914) 995-3333.

- Sterling Community Center Food Pantry for Members: 29 Sterling Ave. (914) 949-1212, M-F 9am-5pm.

- White Plains CAP Food Pantry: 70 Ferris Ave, (914) 428-7030, Hrs. M-Fri 9am-4:30.

Food-Soup Kitchens and Meals:

- Lifting Up Westchester Soup Kitchen: M-F daily meals at 33 Church St 10:30am-11:30am; Food to take home on Friday for weekend, (914)-948-9441.

- Meals on Wheels of WP: 311 N St, #307, (914)-946-6878. eligibility required.

- Salvation Army White Plains Soup Kitchen: Sun 2-2:30pm, 16 Sterling Ave, (914) 949-2908, newyork.salvationarmy.org/location/white-plains-corps/.

- Senior Center: weekly lunch ($3), (914)-422-1423 with reservations.

- Union Food for Life Soup Kitchen: 31 Manhattan Ave, (914) 837-1347 Hrs. Tues 6-7:30pm.

Foster Care:

- United Way 2-1-1: Fostering Parent program: helps with orientations: works with Family Ties & Westchester County.

Free Things:

- Various Facebook groups have free things to be given to those who join.

- White Plains Recycle Yard: Has mulch, fire wood, compost and free items through the TiLi Shed that operates seasonally and has free household items, small furniture, toys, children’s books, sports equipment and much more twice weekly. See White Plains Recycling on website.

Health:

- American Cancer Society: 2 Lyon Pl, (914) 397-8858, acscan.org.

- Burke Rehabilitation Hospital: 785 Mamaroneck Ave, burke.org/community Adult Fitness Program: (M-F 6am to 8:30pm) (Weekends: 8am-4pm), charges depend on needs & programs chosen. Info: (914) 597-2805: Support Groups/Resources

- Care2U.com I 833-433-CARE

- Center for Medicaid & Chip Services: Federal Agency responsible for Medicaid and Child Health Insurance Programs (CHIP) serving low income, children, pregnant women, elderly and people with disabilities determined by each state, In WP, must go through Westchester County. (877) 267 2323, TTY (866) 226-1819. Medicaid.gov, insurekidsnow.gov.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: cms.gov.

- Gatekeeper Program: Designed to bring mobile and off-site services to older adults, 55+, who may need help to improve their mental well-being; need case management. This may include assistance with sadness, anxiety, memory issues, aging needs; substance abuse.

- Gilda’s Club: Cancer Support: 80 Maple Ave, gildasclubwestchester.org, (914) 644-8844,

- Medicaid (for eligible disabled/ low income) Apply through Westchester County

- Medicare (for eligible seniors 65+) Social Security Office & online.

- Medicare Service Center: Providing info about Medicare plans in area and helps locate health care providers that participate in Medicare. (800) 633-4227, TTY (877) 486-2048, mymedicare.gov.

- New York Presbyterian Hospital: 21 Bloomingdale Road, (914) 997-5779, nyp.org/psychiatry, lectures.

- NY Health Complaint/Concerns Call Numbers: Adult Care/ Assisted Living Centers: (866) 893-6772, Ambulatory Surgery Center, Dialysis, Diagnostic Treatment; Primary Care Clinics: (800) 804-5447, Funeral Homes/Directors: (518) 402-0785, Home Care/Hospice: (800) 628-5972, Hospital Patient Care:(800) 804-5447 or health.ny.gov/facilities/hospital, Laboratories: (800) 682-6056, Managed Care Complaints (includes commercial health plans; Medicaid managed care): (800) 206-8125, Nursing Home Hotline: (888) 201-4563, Professional Medical Conduct of Physicians: (800)-663-6114, NYS Office of Medicaid Inspector General; Medicaid Fraud Hotline:(877)-87FRAUD.

- Phelps Hospital: Holistic Pain, Osteoporosis, Childbirth Education & Support Programs. 701 N Broadway, Sleepy Hollow: phelpshospital.org.

- Slater Center: Counseling & Referral Service for individuals & families, M-F 10-4; Senior Drop In Center (M & Thurs 11am-2pm).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: (877) 726-4727, Helps people dealing with mental illness or substance abuse. Connects persons with services through a referral hotline and online treatment center locator. samhsa.gov

- Suicide Prevention (800) 273 8255 TTY (800) 487-4889, samhsa.gov

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline TTY 800 7994889 samhsa.gov

- United Way FamilyWize: card for pharmacy discounts.

- Veterans Administration: 300 Hamilton Ave, first floor, Suite C, (914) 682- 6250.

- Vets White Plains Community Clinic & Women’s health clinic: 23 S Broadway, (914) 421-1952 (x4300).

- Westchester Jewish Community Center: Mental health, trauma, disabilities, youth, home care & geriatric services, 845 N Broadway 914-761-600, www.wjcs.comYWCA: Health and Wellness Programs, 515 North St St, ywcawhiteplains.com, (914) 949-6227.

- Westchester County Department of Senior Programs and Services: NY Connects for info and referrals for long term health care choices. 914-813-6300, Monday – Friday 8:30AM – 4:30PM

- Westchester County Health Dept.: 145 Huguenot St, New Rochelle, (914)-813-5000.

- Westchester Independent Living Center: NY Connects Information and Referral line for long term health care choices, 866-715-4700, Serves seven counties in the lower Hudson Valley: Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, Rockland, Orange, Sullivan, and Ulster. Monday – Friday, 9AM – 5PM

- White Plains Hospital: Support for care givers, Community Health & Wellness programs, lectures, health fairs, Support groups like Overeaters Anonymous, wphospital.org. Located at Davis Ave at Maple Ave/ E. Post Rd.

- ZiphyCare combines advanced technology with the human touch to bring quality medical care into your home—anytime. Provide virtual house-calls for non-emergency conditions: General physical exam· Blood pressure/ hypertension screening· Routine cardiac exam, including EKG· Pulmonary (lung) exam, Dermatologic (skin) exam· Ear (otoscopic) and throat exam. Provide this service at no cost, even if you don’t have health insurance. This service is fully funded by ZiphyCare in partnership with Selfhelp Community Services. Don’t need a computer/smartphone. We handle all the technology for your appointment. If you prefer to schedule on a smartphone, try our convenient Ziphy app (for iPhone or Android).For further information please go to ziphycare.com or call 1-833-ZIPHYCR (1-833-947-4927)

Home Renovation, Repairs and Paying mortgages:

- Bridge Fund of Westchester 914 948-8146

- Catholic Charities Community Services (Westchester) 888-744-7900

- Counseling to Help Homeowners save their home from foreclosure & paying mortgages: Maura Smotrich, Housing Policy Analyst, Tel: (914) 422-6744, email@whiteplainsny.gov

- Landlord Dispute/Mediation: assist tenants and landlords with solutions to prevent litigation: Hudson Valley Justice Center 914 308-3490, Westchester Mediation Center of Cluster 914 963-6440.

- Legal Services of the Hudson Valley 877-574-8529 for eviction cases

- Legal Counseling for eviction prevention and other serives

- New York Affiliates of Habitat for Humanity – through volunteer labor, builds and rehabilitates houses for families in need

- Westchester County Home Renovation Grants: Colette Phipps, LMSW, CDP Director, Program Development Westchester County Department of Senior Programs and Services, (914) 813-6441, Department of Social Services for Rent Arrears, SNAP, medical, other services 914-995-3333, or 914-995-2000 or online at mybenefits.ny.gov

- US Department of Agriculture Rural Development Office – home improvement loans and grants to low-income homeowners in rural areas, Attorney General’s Home Improvement Fact Sheet

- Westchester Residential Opportunities (WRO) 914 428-4507

- Westchester Hispanic Coalition 914 948-8466

- White Plains Home Repairs Help: Westchester Residential Opportunities, Inc, 470 Mamaroneck Avenue (main office), White Plains, NY 10605, Phone: (914) 428-4507, Fax: (914) 428-9455

Housing Help:

- Access to Home for Heroes: Run by Homes & Community Renewal. Provides financial assistance to make dwelling units accessible for low & moderate income Veterans living with a disability. https://hcr.ny.gov/access-home-heroesveterans.

- Habitat for Humanity of Westchester: habitatwc.org,

- My Sister’s Place: https://www.mspny.org, (914) 683-1333, 1 Water St. (for domestic abuse).

- Neighborhood Rehabilitation: (914) 422-1399; planning@whiteplainsny.org, help with repairs; maintenance.

- Salvation Army: 16 Sterling Ave, (914) 948-2908, newyork.salvationarmy.org.

- Westchester Independent Living Center: wilc.gov, (914) 682-3926, (914) 259-8036 (VP/TTY), e-mail wilc.org.

- Westchester Residential Opportunity: 470 Mamaroneck Ave, Housing counseling & assistance, https:www.wroinc.org, (914) 928-4027.

- Westchester Coalition for Hungry and Homeless: 48 Mamaroneck Ave, (914) 682-2737, westchestercoalition.org.

- Westchester Habitat ReStore of Mt Vernon, 659 Main St, New Rochelle, (914) 699-2791, restorewestchester@gmail.com, furniture & other things.

- Westhab: Westchester County Provider of housing and supportive services for low-income people, 13 Longview Ave, (914) 682-1458, westhab.org/.

- White Plains Building Department: (914) 422-1269, Enforcement Issues of City Ordinances and housing issues.

- White Plains Housing Authority (Sec 8; affordable housing): 223 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard, (914) 949-6462, wphany.com.

Info Helplines:

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information Line: (202) 307-0663, (800) 514-0383 (M-W and F 9:30am- 5:30pm, Th 12:30-5:30pm, TTY (800) 514-0383, ada,gov. Answering questions about ADA Standards for Accessible Designs and about ADA requirements.

- Child Abuse Reporting Hotline: NY State Central Register and online resource for help with government resources, (800) 342-3720

- Domestic Abuse Hotlines: Westchester County Office for Women 914 995-5972

My Sister’s Place, (800) 298-723. (domestic abuse). - Economic Crimes Bureau: (914) 995-3303 (through of Westchester District Attorney’s Office)

- Elder Abuse Bureau Hotline: (914) 995-3000 (Westchester District Attorney’s Office)

- Elder Abuse Helpline (914) 813-6436 (through of Westchester County)

- Elder Abuse Prevention & Victim Assistance Program was created to assist survivors of elder abuse (physical, emotional, sexual, financial or neglect), 50+, or who are at risk of abuse & not in immediate crisis. Contact: Nicolle Brunale, LMSW, (914) 668 – 9124 x28

- Emergencies: 911

- Hebrew Home ElderServe: 24 hour hotline (800) 567-3646

- Here to Talk Listen & Support: 1-844-863-9314 for emotional Support Helpline Online Support Groups; Website Resources

- HIV.gov: HIV/AIDS works to increase knowledge; access to services for at risk people living with HIV.

- National Health Information Center: (240) 454-8280, e-mail at nhic@hhs.gov. health.gov/nhic, healthfinder.gov, or healthfinder.gov/espanol.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255, suicidepreventionlifeline.org

Veterans Crisis Center: (800)-273-8255 (press 1). - NY Connects: nyconnects.ny.gov/home. 800-342-9871

- NYProjectHope.org: Confidential | Anonymous | Free

- Pace Women’s Justice Center Helpline: For victims and survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault and elder abuse, (914) 287-0739, law.pace.edu/wjc.

- Protective Services for Adults: (914) 995-2259 (through Westchester County)

- US Health & Human Services Fraud Hotline: (800) 447-8477, TTY (800) 277 4950. Office of Inspector General protecting the integrity of Health and Human Services. oig.hhs.gov or stopmedicarefraud.gov.

- United Way 2-1-1: Dial 211 for help (food, utilities, abuse, recycling regulations, becoming foster parents & getting medical assistance, (914)-997-6700.

Legal- Discrimination Help:

- Child Support Hotline (part of Legal Services): (844) 949-1305 1:30-4:30PM Tuesday & Thursday.

- Human Rights Commission: 7-11 S Broadway, Suite 314, acts on discrimination in employment, housing, places of public accommodation.

- Legal Services of the Hudson Valley: 90 Maple Avenue, (914) 949-1305, 9AM-5PM, Help line: (877) 574-8529 (M-Thurs 8am-6pm) (Friday 8am-4pm)

- Legal Services of the Hudson Valley Preventing Evictions: 90 Maple Ave, M-F 9-5. (914) 949-1305.

- Office for Civil Rights: (800) 368-1019, TTY (800) 537-7697 e-mail at ocrmail@hhs.gov, Website: hhs.gov/ocr. Discrimination in healthcare & social service programs; privacy of your health information.

- Pace Women’s Justice Center Helpline: (914) 287-0739

- YWCA: Racial Justice, 515 North St, ywcawhiteplains.com, (914) 949-6227.

- Westchester Legal Aide: 150 Grand St, Suite 1, (914) 682-4112

Mental Illness:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness: 100 Clearbrook Rd. #181, Elmsford NY, (914) 592-5458100 namiwestchester.org

Safety:

- Life Support Equipment & Medical Emergencies: Con Ed keeping life support equipment working through storms or other emergencies, (800) 752-6633, coned.com, Requires certification by doctor or local board of health call to (718) 222-7593 each yr.

- WP Alerts: Enroll for mobile or land phone emergencies in area, cityofwhiteplains.com/index.aspx?nid=504

- White Plains Public Safety: wppublicsafety.com, (914) 422-6111.

Transportation:

- American Cancer Society-Road to Recovery: 800-227-2345, cancer.org/treatment/supportprogramservices/road-to-recovery, provides ground transportation for cancer related medical appointments at no charge. Must be able to go without assistance or bring a person to help.

- Cancer Support Team: 2900 Westchester Ave, Suite 103, Purchase NY, (914) 777-2777, contact Paulina Arriaga or Gini Ricca.

- Lighthouse Guild Travel Safety Program: (212) 769-6291 e-mail MoogC@lighthouseguild.org.

- Medicaid Transportation: Answering Services LLC (800) 850-5340 medanswering.com for eligible persons.

- Paratransit of Westchester County: (914) 995-7272 (press 2), use of taxi or van with application filed and processed.

- RideConnect Westchester: rideconnectwestchester.org, (914) 242-7433, free volunteer rides to 60+.

- TRA: medical appointments for older adults; visually impaired adults. (914) 764-3533, info@my-TRA.org

- WestFair Rides: For 60+ visually impaired (914)764-3533 westfairrides.org.

- Westchester Jewish Community Services: Project Time Out, (914) 761-0600 (ext. 310) website: wjcs.com, Respite help to caregivers to provide 60+ adults within home respite & escort services.

- Westchester County Bee-line System, Senior and Disabled services: transportation.westchestgov.com/senior-and-disabled-services, (914) 814-7777. Seniors and Disabled can apply for reduced fares. B.E.A.T. for seniors is a program to help seniors use Bee-line System (914) 813-7741 or use website transportation.westchestergov.com/transit-education/senior-b-e-a-t.

Work:

- Career Support Solutions: For further info contact: Allison Scorca, (914) 741-8500 X106 or e-mail ascorca@careersfp.org or www.CAREERSSupportSolutions.org

- Center for Career Freedom:185 Maple Ave., Ste #124, White Plains, NY 10601, (914) 288-9763, free training; employment agency

- Grants for Minority Businesses: https://suppliedshop.com/blogs/articles/minority-small-business-grants

- NY Labor Department.: Services to protect workers, assist unemployed & connect job seekers to jobs. 120 Bloomindale Rd, labor.ny.gov/home/. Free Language Assistance at 1-(888) 469-7365.

- Score Westchester: Advisory & Small business mentoring for people wanting to start or grow a small business, 120 Bloomingdale Rd at NYS Dept. of Labor, scorewestcheser.com and for Scores list of resources: https://www.score.org/resource/list-startup-resources.

- SCSEP – Senior Community Service Employment Program: For more information contact Shelly Ameri, Career Counselor, The WorkPlace – 203-340-2312/ rameri@workplace.org.

- WEBS Career & Educational Counselling Service: 570 Taxter Rd. Elmsford, (914) 674- 3600, westchesterlibraries.org/career-educational-counseling-services/, Help planning career path.

- Westchester Putnam One Stop Career Center: 120 Bloomingdale Rd, 914 995-3910 whiteplainslibrary.org/white-plains-resources/categories/all/

- White Plains Education Training Center: 303 Quarropas St, (914) 442-8200, e-mail wpetc@whiteplainsny.gov, (914) 422-8200, http://www.cityofwhiteplains.com/index.aspx?nid=636 for newsletter, info, training & workshops; Career Closet for clothing at Center

- Women’s Enterprise Development Center, Inc: https://wedcbiz.org/, 914 948-6098, 1133 Westchester Ave. Empowers entrepreneurs to build businesses by providing training, advisory services & access to capital.

- Yes She Can, Inc: Assistance to teen girls & young women with autism spectrum disorders to develop job skills for competitive work and to achieve greater independence, 4 Martine Ave, Store2B yesshecaninc.org.

Workouts or Exercise Programs:

- GetSetUp :NY State Office For The Aging & Association on Aging in NY and to provide free virtual classes for older adults taught by peers – ask questions, make friends, learn new things, and have fun. www.getsetup.org/partner/NYSTATE, use coupon code: NYSTATE, 1-888-559-1614/ info@getsetup.io

- YWCA of White Plains and Central Westchester is inviting you to free wellness classes offered to breast cancer survivors and patients. Please register first for this class by contacting Ned Corona at ncorona@ywcawpcw.org

White Plains Demographics

White Plains (WP) today is a “diverse” community but has not always been. Census reporting gives the best way to examine the changes.

WP’s first settlers came from Rye in 1683 and were English Puritans. The first US census of 1790, recorded WP with a total population of 550. This number included 40 slaves. In 1820, WP had 675 residents of which 63 were free blacks and 8 slaves. After 1827, slavery ended in NY and the Census recorded a population of 2,630.

The population of WP grew after the NY and Harlem Railroad reached WP on Dec 1, 1844. The population in 1880 was 2,381 and went up 60.8% by 1890 to 4,042. By 1900, the population had increased by 90.5 % to 15,045. The Harlem rail line to WP became electrified by 1910 and a second rail line the NY, Westchester and Boston Railway opened in 1912. This line ran through the center of WP from its southern border with Scarsdale to Westchester Ave (where Nordstrom is today). The train companies advertised the availability of affordable lots where one could build a home. They also offered deals for weekly committing options and the attractiveness of area for permanent leisure living and for shorter vacations (holidays, summers and weekends).

In 1920, WP had 21,031 residents. By this time, WP had other forms of faster more convenient modes of transport with buses (replacing trolleys) and cars. The NY, Westchester Boston railway closed in 1937. In 1930, WP’s population was 35,830. The NY Westchester Boston railroad stopped running in 1937 but had no affect on the population. In 1940, WP had 40,327 and in 1950 43,466. Winbrook Apartments (now named Brookfield Commons) opened in 1950 giving the WP low income housing choices.

The population of WP increased to 50,485 by 1960 and though the Cross Westchester opened the population in WP decreased. A major urban renewal project began in the core area of the Business District with demolition beginning around 1966 and continued till 1980. Eliminated in the Business District were blocks of structures containing housing and businesses. As a result, many African Americans and Italians left the city. By 1970, the population had decreased .3% to 50,125 and by 1980 it fell to 46,999. City had more low income rental housing choices in areas outside the Business District but it was still hard for Blacks (and others) to secure loans for home ownership and to purchase single family houses in WP.

By 1980, much of the Business District had been transformed and the number of residents began to increase again. By 1990 the population had increased to 48,718.

By 2000, WP had 53,077 residents. The racial break down was 34,465 White(64.9%), 8,444 Black or African American (15.9%), 182 American Indian/Alaskan Natives (.3%), 2,389 Asian (4.5%), 37 Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (.1%), 5,502 from other races (10.4%) and 2,058 from 2 or more races (3.9%). Of the total, 12,476 or 23.5% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

By 2010, the population was 56,853. The city’s racial make-up: White 36,178 (63.6%), 8,070 Black or African Americans 8,070, 394 American Indian/Alaska Native (.7%), 3,623 Asian (6.4%), 20 Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (less than .1%), 6,324 of other races (11.1%) and 2,224 from 2 or more races (3.9%). Of that, 16,839 are Hispanic or Latino of any race (29.6%).

Population estimates projected by US Census Bureau and this and other information is available on the website: http://www.census.gov. Estimate for 2017 (in July) is 59,047 residents.

*Data from US Census Bureau American FactFinder for 2000 and 2010.

History Behind the Curtain: Broadway Theatre

First play I went to see as a teen was Fiddler on the Roof and I was hooked. Continued to go to live theatre during my college years including Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven as well as student productions of Southern Connecticut College where I attended school from 1972 to 1975. In 1982, I became a TDF member that gave me access to a lot of live shows on and off Broadway.

Most Broadway theatres are historic; treasures that I hope will be preserved for a long time. Broadway Theatres are defined by their size (number of people in the audience) and the quality of the performance. Musicals require live musicians. The smallest theatres seat about 500 but many seat over a thousand. Most are in the Theatre District (W 40th St to W 54th St) of NYC but the Vivian Beaumont Theater is at Lincoln Center.

Many of the 41 Broadway Theatres are named after producers, actors and others associated with the theater.

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

The 1925 theatre at 261 W 47th St is named for publicist Samuel J. Friedman.

Ethel Barrymore Theatre:

The 1928 theater at 243 W 47th St is named after actress Ethel Barrymore.

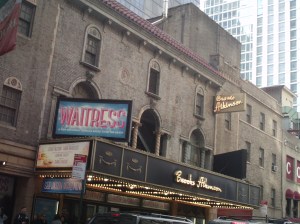

Brooks Atkinson Theatre:

The 1926 theatre at 256 W 47th St is named after NY Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson.

Wonderland

Posted on March 7, 2018 by sandraharrison1954

Leave a Comment

No, I’m not Alice.

Feeling more like a Mad Hatter.

I do know, though,

That I’m not in Kansas.

Can’t stop watching,

The drama taking place in the Capital.

The bad guys seem to be winning.

Protesting doesn’t seem to matter

Though protestors at Capital hearings seem out of place.

America has done itself harm,

By electing the most disrespectful,

Dishonest fool that I have ever known.

And, the anger and hate that has followed is scary.

It’s like being in a long dark tunnel

With no end in sight.

Creepy crawlers all about.

Just looking for truth and hope.

Don’t usually follow the process of selecting our nation’s Cabinet secretaries

But I was curious

Like a moth drawn to the light.

Once the Senate votes in a bunch of billionaires

The country will be in the hands of a bunch of billionaires

Who live in a world so far removed from the rest of us.

.

Share this: Sandy's Written Creations